Nov. 5, 2020

Nassim Taleb has this idea of

"convexity".

There's a bunch of complicated maths but it's actually quite a simple

concept once you get it. This concept is useful for indie hackers and

people bootstrapping businesses, because it gives you a general strategy

that works in the presence of high levels of uncertainty (i.e. real life).

Is your business idea any good? Is there a market? Is the timing right?

None of these questions matter so much if you choose convex processes.

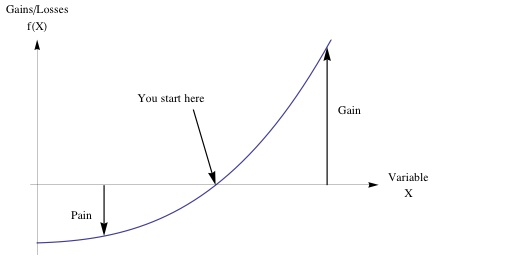

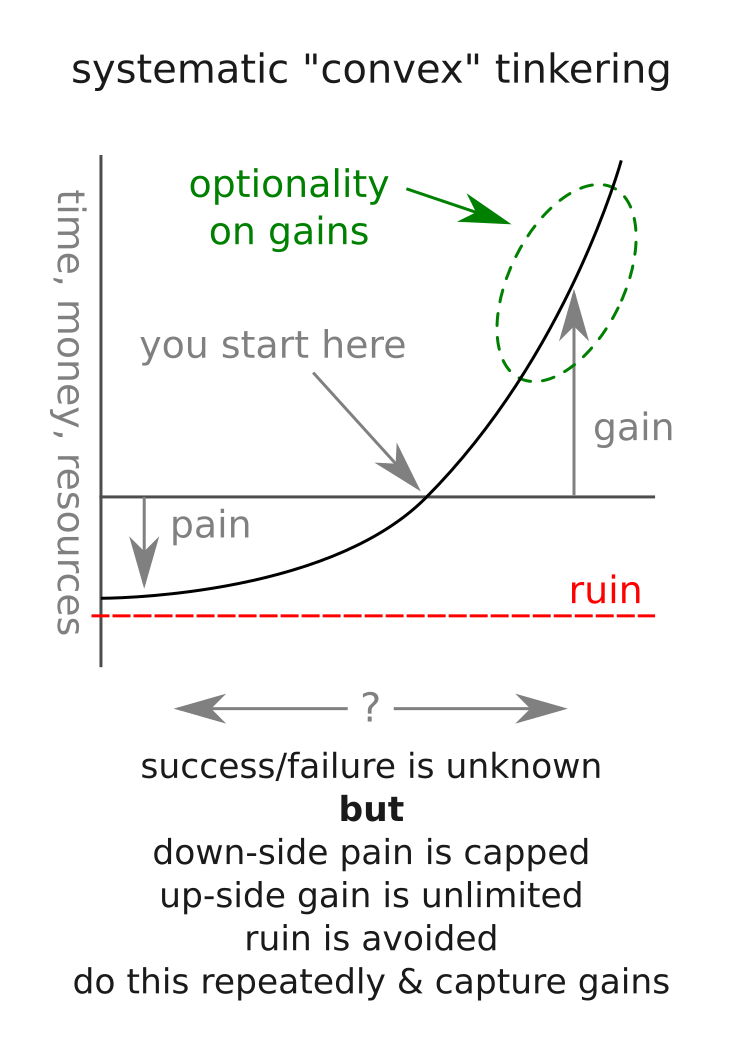

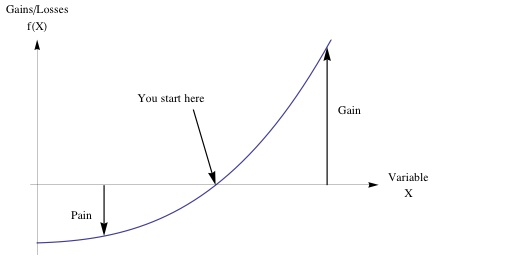

So what is convexity? If a process is convex it means it has a big

potential up-side and a limited potential down-side. Take a look at this

graph and imagine your project is a marble that is pushed randomly to

the left or right.

If it is given a push to the left then it will roll down the slope. If

it is given a push to the right it will go up the slope. You can clearly

see that there is a maximum depth the marble can go if it goes left, but

it can go much higher if it goes to the right. Given enough force to the

right it's going to fly off and your project will make a million

dollars! So the down-side is limited, but the up-side is unlimited.

If some activity maps to this graph then you can say it's convex and

those are the types of things you want to do. What you want to avoid is

activities or processes where the opposite is true: all pain and no gain.

One of Taleb's insights is that we should not worry about the direction

of the push on the marble because we simply can't know it. It's an

uncertain world and the force on the marble is effectively random. We

only fool ourselves if we pretend to be able to predict it. How many

times have you launched something or tweeted or posted and not had the

result you expected? You're going to be wrong a lot. Convexity

embraces being wrong a lot.

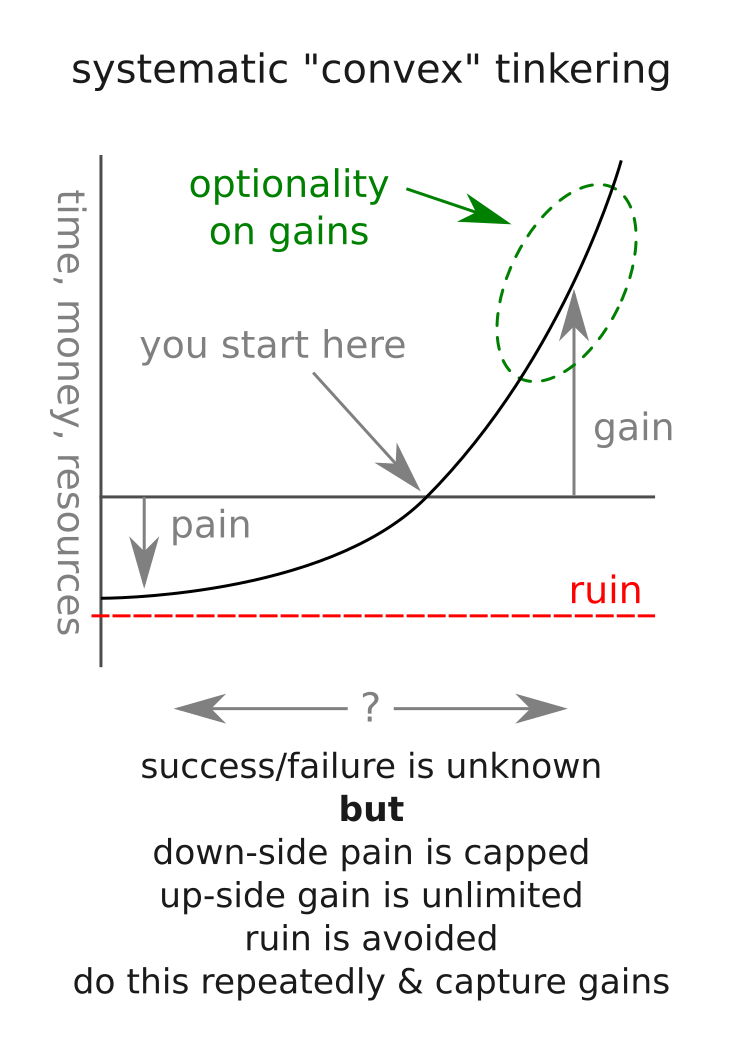

So how does this apply to bootstrapping a business? All you gotta do is

make sure you are picking convex activities at each step of your

project. Decide if a given process or activity or action has a limited

down-side and an unlimited up-side, and do it if so. Do lots of these

convex activities to uncover reliable up-side and run-away successes.

Non-convex indie hacker processes (bad)

Here are some examples of non-convex indie hacker processes that you

should avoid:

Quitting your job to go all-in on your unprofitable side project.

This is non-convex because the down-side is ruin. If things go wrong you

end up on the street with no job and a failed startup.

Spending a long time building without shipping. This is non-convex

because the down-side is a loss of an unbounded amount of your most

precious resource: your time on this earth.

Taking VC funding. Contraversial I know, but I beleive this is

non-convex because you are locked into one business, beholden to the

whims of investors, and you have given up all optionality (another Taleb

idea I'll discuss below). Basically there is unlimited down-side in

being beholden to somebody else's goals and not being able to do

anything about it because they hold the purse strings.

Taking out a bank loan before you have paying customers. Taking on

debt seems to be non-convex generally because of the unbounded way debts

can grow.

Convex indie hacker processes (good)

Retaining some freelance hours while you work on side projects. This

is convex because the down-side is limited (you still get to eat if you

fail) and the up-side is unbounded if one of your side projects takes off.

Time-boxing your development and shipping frequently. This is convex

because the time you lose if you build something that nobody wants is

capped, but something you ship might actually catch on.

Posting on Twitter, Hacker News, and marketing in general. Marketing

is convex because there is only a small amount of reputational risk and

you have to be reeeally annoying to reach that level. The unbounded

upside is having your product discovered by a market that really wants it.

Building in public. This is convex for the same reason as marketing.

If you fail, or look like a fool, it's just not that bad. Upside is

exposure, reputation, and viral adoption of what you're doing.

12 startups in 12 months. This strategy looks insane but if you look

at how it works out for somebody like Pieter Levels it is convex. It's

common for people to not finish their 12 startups and often the reason

is because they also have the option to exit early on success (see

below). It's a safe way to practice Taleb's "systematic convex tinkering".

Optionality

Another property you want is optionality. Let's take the Pieter Levels

12-startups-in-12-months example. Here you not only have convexity but

you also have the option to take one of the 12 startups and run with

it. Nobody is going to care if you stop at startup number 7 because it

became a raging success that demands your attention. This is in fact

exactly what Levels did. He launched Nomad List and Remote Ok, and then

when it was clear they were popular, he took the option and went back

and pumped them up.

So you also want to do things where you have the option to retain any

up-side that is achieved.

Marketing is another good example. Lets say you post on Hacker News ten

times and nine of those times you hear crickets, but one of the times

your post blows up. Optionality means capturing that attention somehow

so you can use it again later. So for example you might have an email

list that people can opt in to. When a post does well you capture the

up-side by letting interested people subscribe to your list.

Side note: are successful founders just lucky?

Elsewhere Taleb and Ole Peters and others talk about the concept of

ergodicity, and two different types of probability: time vs. ensemble.

Ensemble probability is when you look at all indie hackers, and then the

sub-set of "successful" indie hackers, and then figure out the

probability of indie hacker success based on those two numbers. When I

wrote that post which blew

up

it was about the ensemble probability of indie hackers, so it is

actually a bit misleading because ensemble probability is the wrong way

to look at it.

Time based probability is when you take a single indie hacker running

many experiments, and look at their journey over time. It's the

probability that one of their business experiments goes big.

The safest place to be is in the second category, running many convex

experiments over time with no chance of ruin on any given experiment.

You want to take the time based view because that is the one you

actually have in real life. You are one single person, not many people

in parallel.

Some successful founder stories are actually only visible in the

ensemble category. They made one thing, got the golden ticket, and made

a million dollars.

When taking the advice of successful founders you would do well to look

at whether they are ensemble or time based. Did they try a ton of

different ideas before succeeding? Good. Have they had more than one

success or just one? Time based successes are the ones you want to learn

from because they are repeatable. Individual successes from the ensemble

are less useful as they may be due to good luck rather than good processes.

Conclusion

Run many business experiments sequentially, cap the down-side

(time/cost/ruin), retain the option to capture any up-side.

Good luck! You won't need it.

PS You have the option of following me on

twitter to find out about stuff I'm making. ;)

Footnote: I hope I have understood Taleb's ideas correctly, but if I

have made any mistakes they are 100% my own.