Here are some illustrated explanations of the main ways in which cryptographic hash functions can be attacked, and be resistant to those attacks.

Zooko Wilcox's blog post Lessons From The History Of Attacks On Secure Hash Functions gives us a nice overview of these and I've quoted his concise explanations below. Check out his great post for more detail and history on this topic.

A cryptographic hash function is an important building block in the cryptographic systems that keep us safe in our communications on the internet.

A hash function takes some input data and generates a hopefully unique string of bits for each different input. The same input always generates the same result.

The input to a secure hash function is called the pre-image and the output is called the image.

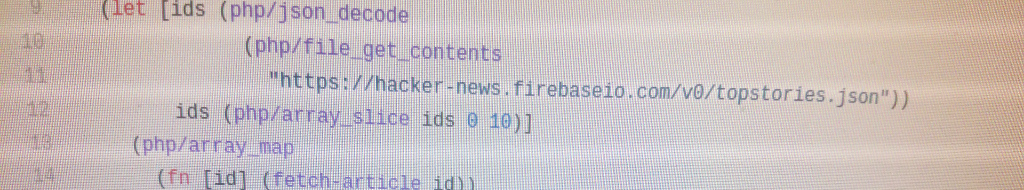

I use the following key below:

Red for inputs which can be varied by an attacker.

Green for inputs which can't be varied under the attack model.

To attack a hash function the variable inputs are generally iterated on in a random or semi-random brute-force manner.

Collision attack

A hash function collision is two different inputs (pre-images) which result in the same output. A hash function is collision-resistant if an adversary can't find any collision.

Pre-image attack

A hash function is pre-image resistant if, given an output (image), an adversary can't find any input (pre-image) which results in that output.

Second-pre-image attack

A hash function is second-pre-image resistant if, given one pre-image, an adversary can't find any other pre-image which results in the same image.

Hopefully these diagrams help to clarify how these attacks work!